John Sweet is at his best when he is at his darkest. And that's where

he usually is. He puts before the reader a backdrop of unrelenting darkness.

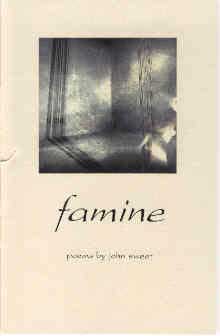

In famine, a book with no capital letters and no punctuation, there

are no adornments. The lines of poetry are as stark as the character

set they are made from.

But, against this backdrop, there is something that, for want of a better

term, I'll call 'light.' What is this light, what are its properties,

and how does it happen at all?

The opening poem in famine is called "mapping the 21st century:

notes for the disappeared." A central theme in this poem is the

disappearance of a girl. About two-thirds of the way through the poem,

we come to these lines:

the dogs are hungry

but no one thinks to feed them

no one thinks

to put out the fire and

the girl is gone

is nothing more than

a blurred smiling face nailed

to every telephone pole in

a town i never want to

walk through

You don't have to read further to know that there is no happy ending

here. In fact, in this poem, you can't read much further. There are

only three more lines—as the poet claims the town that he doesn't

want to walk through:

what it looks like

from this distance is

my own

The death that he sees projected on the telephone poles is eventually

to be his own too. And ours. We don't think about it most of the time.

Probably John Sweet doesn't either. In his poetry, he never forgets

it.

In "where the word is almost spoken," an earlier poem that

preceded this collection, he establishes the coloration of a scene:

where the sun is a

thin wash of grey

in dali's sky

And it's the right coloration. But it is the 'word' that is the prevailing

topic. The poem ends this way:

and the word is hope

and it will be

forgotten

and all of us

with it

of this much

i'm sure

Being a dedicated and unrepentant re-reader, I was reading those lines

for the Nth time when I felt the full impact of his work. I mean I felt

something very much like the flicker of an upswing in my mood. Why?

Like most people, or maybe all people, I wish things would work out

somehow. Then why did those lines make me feel good?

I think it starts as a form of contrast. Sweet's relinquishing of every

hope creates a darkness so intense that something contrasting takes

shape in front of it. It's very much like the formation of a secondary

image, a complementary color, after you look at a fluorescent hue. When

you stare at an intense green, you soon see an aura of red. When I look

into the blackness of Sweet's poems, I come to a point when I suddenly

see light.

But that's just the phenomenon. The next question that comes up is 'what

is this light?' Is it the persistence of hope, after all? Or is it a

release from hope? A feeling of being freed for a moment from the suspense

of hoping, against all apparent odds, that somehow things will work

out? Or am I jolted into seeing more dimensions of the awful mystery

we live in—or, at least, do I get a glimmer of that and feel it

as a nameless exhilaration? Or is it something else altogether?

I don't intend to suggest an answer. What impresses me about Sweet's

poetry is that it brings me to that sensation, brings me to those questions,

and leaves me to consider.

Despite his prevailing tone, not all of his poems are entirely dark.

Among the works in famine is one called "poem with light and form,

but no direction." Early in this poem, Sweet's theme is as fatal

as ever.

of fathers

raping their daughters and

murdering their sons

Then, after a skillful transition in tone and focus, in which the poet

steps back from his description of a demented world, the poem closes

with these two stanzas:

except that maybe

my wife

begins to love me again

my hands suddenly alive

with the possibility

of hope

It's engaging to hear him vary his tone to write lines of affection—and

these, in particular, have a terrific vitality. Obviously they're not

complacent valentine lines. They carry the image of a past sundering

between the speaker and his wife. And, even here, to hope is only a

possibility. To have your hopes fulfilled has to be more distant yet.

And there's this—his 'possibility of hope' offers me an emergency

exit in those other poems where he seems to blot out all hope. Still,

because of the power of his gloom, I find myself hoping that he stays

mostly with his darkest poems.

Often it is his low-key lines that are the most desolate. I think of

"a random progression" (also in famine) where I read lines

of violent brutality at the beginning. Then, near the end, I come to

this:

...a woman in a house

filled with shadows checks

the clock beside her bed

John Sweet comes through as a very honest poet—as someone who

values an unadorned reality, and who presents the world as he sees it.

And, whether through his intent or through some inevitable organic side

effect of his poetry, his dark vision irresistibly evokes something

that I have to call hope. I also see, behind his frequent preoccupation

with lost or slain children, an intrinsic caring—perhaps the kind

of caring felt by someone in touch with his own childhood—a feeling

that he never exploits, never reduces to sentimentality. Most of all,

he is an artist who journeys into absolute doom—and comes back,

bringing vital poetry with him.

The chapbook, famine, is not very long. It contains 20 poems, each on

a single page. I think these 20 poems are very worth reading, and I

would recommend this book to any reader of serious poetry.

|